Debates about mining and the environment are often framed in terms of a "nexus" between the resources that are extracted and the resources needed to dig them up. But too few people, including policymakers, truly understand the relationship between a low-carbon future and the mining industry that will deliver it.

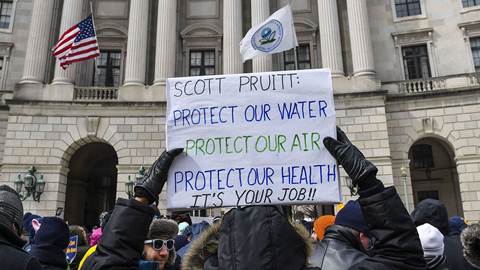

LONDON – Donald Trump’s presidency in the United States has turned mining – and the coal industry in particular – into a political cause célèbre over the last year. In June, during his first White House cabinet meeting, Trump suggested that his energy policies were putting miners back to work and transforming a troubled sector of the economy.

But Trump is mistaken to think that championing the cause of miners and paying respect to a difficult profession will be sufficient to make mining sustainable. To achieve that, a far more complex set of interdependencies must be navigated.

Debates about mining and the environment are often framed in terms of a “nexus” between extraction of a resource and the introduction of other resources into the extraction process. The forthcoming Routledge Handbook of the Resource Nexus, which I co-edited, defines the term as the relationship between two or more naturally occurring materials that are used as inputs in a system that provides services to humans. In the case of coal, the “nexus” is between the rock and the huge amounts of water and energy needed to mine it.

For decision-makers, understanding this linkage is critical to effective resource and land-use management. According to research from 2014, there is an inverse relationship between the grade of ore and the amount of water and energy used to extract it. In other words, misreading how inputs and outputs interact could have profound environmental consequences.

Moreover, because many renewable energy technologies are built with mined metals and minerals, the global mining industry will play a key role in the transition to a low-carbon future. Photovoltaic cells may draw energy from the sun, but they are manufactured from cadmium, selenium, and tellurium. The same goes for wind turbines, which are fashioned from copious amounts of cobalt, copper, and rare-earth oxides.

Navigating the mining industry’s resource nexus will require new governance models that can balance extraction practices with emerging energy needs – like those envisioned by the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Value creation, profit maximization, and competitiveness must also be measured against the greater public good.

Some within the global mining industry have recognized that the winds are changing. According to a recent survey of industry practices by CDP, a non-profit energy and environmental consultancy, mining companies from Australia to Brazil are beginning to extract resources while reducing their environmental footprint.

Nonetheless, if the interests of the public, and the planet, are to be protected, the world cannot rely on the business decisions of mining companies alone. Four key changes are needed to ensure that the industry’s greening trend continues.

First, mining needs an innovation overhaul. Declining ore grades require the industry to become more energy- and resource-efficient to remain profitable. And, because water scarcity is among the top challenges facing the industry, eco-friendly solutions are often more viable than conventional ones. In Chile, for example, copper mines have been forced to start using desalinated water for extraction, while Sweden’s Boliden sources up to 42% of its energy needs from renewables. Mining companies elsewhere learn from these examples.

Second, product diversification must start now. With the Paris climate agreement a year old, the transformation of global fossil-fuel markets is only a matter of time. Companies with a large portfolio of fossil fuels, like coal, will soon face severe uncertainty related to stranded assets, and investors may change their risk assessments accordingly.

Large mining companies can prepare for this shift by moving from fossil fuels to other materials, such as iron ore, copper, bauxite, cobalt, rare earth elements, and lithium, as well as mineral fertilizers, which will be needed in large quantities to meet the SDGs’ targets for global hunger eradication. Phasing out coal during times of latent overproduction might even be done at a profit.

Third, the world needs a better means of assessing mining’s ecological risks. Although the industry’s environmental footprint is smaller than that of agriculture and urbanization, extracting materials from the ground can still permanently harm ecosystems and lead to biodiversity loss. To protect sensitive areas, greater global coordination is needed in the selection of suitable mining sites. Integrated assessments of subsoil assets, groundwater, and biosphere integrity would also help, as would guidelines for sustainable resource consumption.

Finally, the mining sector must better integrate its value chains to create more economic opportunities downstream. Establishing models of material flows – such as the ones existing for aluminum and steel – and linking them with “circular economy” strategies, such as waste reduction and reuse, would be a good start. A more radical change could come from a serious engagement in markets for secondary materials. “Urban mining” – the salvaging, processing, and delivery of reusable materials from demolition sites – could also be better integrated into current core activities.

The global mining industry is on the verge of transforming itself from fossil-fuel extraction to supplying materials for a greener energy future. But this “greening” is the result of hard work, innovation, and a complex understanding of the resource nexus. Whatever America’s coal-happy president may believe, it is not the result of political platitudes.

LONDON – Donald Trump’s presidency in the United States has turned mining – and the coal industry in particular – into a political cause célèbre over the last year. In June, during his first White House cabinet meeting, Trump suggested that his energy policies were putting miners back to work and transforming a troubled sector of the economy.

But Trump is mistaken to think that championing the cause of miners and paying respect to a difficult profession will be sufficient to make mining sustainable. To achieve that, a far more complex set of interdependencies must be navigated.

Debates about mining and the environment are often framed in terms of a “nexus” between extraction of a resource and the introduction of other resources into the extraction process. The forthcoming Routledge Handbook of the Resource Nexus, which I co-edited, defines the term as the relationship between two or more naturally occurring materials that are used as inputs in a system that provides services to humans. In the case of coal, the “nexus” is between the rock and the huge amounts of water and energy needed to mine it.

For decision-makers, understanding this linkage is critical to effective resource and land-use management. According to research from 2014, there is an inverse relationship between the grade of ore and the amount of water and energy used to extract it. In other words, misreading how inputs and outputs interact could have profound environmental consequences.

Moreover, because many renewable energy technologies are built with mined metals and minerals, the global mining industry will play a key role in the transition to a low-carbon future. Photovoltaic cells may draw energy from the sun, but they are manufactured from cadmium, selenium, and tellurium. The same goes for wind turbines, which are fashioned from copious amounts of cobalt, copper, and rare-earth oxides.

Navigating the mining industry’s resource nexus will require new governance models that can balance extraction practices with emerging energy needs – like those envisioned by the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Value creation, profit maximization, and competitiveness must also be measured against the greater public good.

SUMMER SALE: Save 40% on all new Digital or Digital Plus subscriptions

Subscribe now to gain greater access to Project Syndicate – including every commentary and our entire On Point suite of subscriber-exclusive content – starting at just $49.99

Subscribe Now

Some within the global mining industry have recognized that the winds are changing. According to a recent survey of industry practices by CDP, a non-profit energy and environmental consultancy, mining companies from Australia to Brazil are beginning to extract resources while reducing their environmental footprint.

Nonetheless, if the interests of the public, and the planet, are to be protected, the world cannot rely on the business decisions of mining companies alone. Four key changes are needed to ensure that the industry’s greening trend continues.

First, mining needs an innovation overhaul. Declining ore grades require the industry to become more energy- and resource-efficient to remain profitable. And, because water scarcity is among the top challenges facing the industry, eco-friendly solutions are often more viable than conventional ones. In Chile, for example, copper mines have been forced to start using desalinated water for extraction, while Sweden’s Boliden sources up to 42% of its energy needs from renewables. Mining companies elsewhere learn from these examples.

Second, product diversification must start now. With the Paris climate agreement a year old, the transformation of global fossil-fuel markets is only a matter of time. Companies with a large portfolio of fossil fuels, like coal, will soon face severe uncertainty related to stranded assets, and investors may change their risk assessments accordingly.

Large mining companies can prepare for this shift by moving from fossil fuels to other materials, such as iron ore, copper, bauxite, cobalt, rare earth elements, and lithium, as well as mineral fertilizers, which will be needed in large quantities to meet the SDGs’ targets for global hunger eradication. Phasing out coal during times of latent overproduction might even be done at a profit.

Third, the world needs a better means of assessing mining’s ecological risks. Although the industry’s environmental footprint is smaller than that of agriculture and urbanization, extracting materials from the ground can still permanently harm ecosystems and lead to biodiversity loss. To protect sensitive areas, greater global coordination is needed in the selection of suitable mining sites. Integrated assessments of subsoil assets, groundwater, and biosphere integrity would also help, as would guidelines for sustainable resource consumption.

Finally, the mining sector must better integrate its value chains to create more economic opportunities downstream. Establishing models of material flows – such as the ones existing for aluminum and steel – and linking them with “circular economy” strategies, such as waste reduction and reuse, would be a good start. A more radical change could come from a serious engagement in markets for secondary materials. “Urban mining” – the salvaging, processing, and delivery of reusable materials from demolition sites – could also be better integrated into current core activities.

The global mining industry is on the verge of transforming itself from fossil-fuel extraction to supplying materials for a greener energy future. But this “greening” is the result of hard work, innovation, and a complex understanding of the resource nexus. Whatever America’s coal-happy president may believe, it is not the result of political platitudes.