Policymakers, academics, and journalists have been discussing the global financial crisis and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as if they somehow existed on parallel tracks. But today’s financial and foreign-affairs crises are closely linked.

NEW YORK – Policymakers, academics, and journalists usually discuss the global financial crisis and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as if they somehow exist on parallel tracks. But today’s financial and foreign-affairs crises are in fact closely linked. Indeed, the way the world has sought to resolve the financial crisis offers interesting insights about how the foreign-affairs crisis should be approached.

Today’s foreign-affairs crisis goes well beyond Afghanistan and Iraq. The record of countries that move from conflict to a fragile peace through military intervention or negotiated settlements is dismal: roughly half of them revert to conflict, leading to more human tragedy and large numbers of refugees. Moreover, failed states are an incubator for terrorism, trafficking of drugs and people, piracy, and other illicit activities. Of the half that remains at peace, the large majority end up highly dependent on foreign aid – hardly a sustainable model in the context of the global financial crisis.

The two crises have created immense human suffering worldwide: thousands of families have lost loved ones in wars, and the financial crisis has taken people’s jobs, livelihoods, assets, pensions, and dreams, as well as worsening fiscal and debt conditions in most industrial countries. As a result, taxpayers in donor countries are demanding more transparency and accountability in how their money is spent both domestically and abroad – and rightly so.

There are notable links between the two crises. The war in Iraq contributed in part to the increase in oil prices from $35 per barrel in 2003 to $140 in 2007. This increase put pressure on businesses and consumers, and was a major factor in the increase in world food prices. As prices went up and recessionary pressures increased, many homeowners failed to pay their mortgages. The sub-prime sector in the United States was hit, and the financial crisis spread from there.

Both crises require policymaking that departs from “business as usual.” Short-term emergency policies are needed to deal with high unemployment, home foreclosures, business bankruptcies, and often with hunger, disease, and a number of other ills. Emergency or humanitarian policies may improve basic consumption in the short run, but they may also discourage investment, increase inflation, and lower prospects for economic in the long run. As a result, such policies should be discontinued as soon as possible.

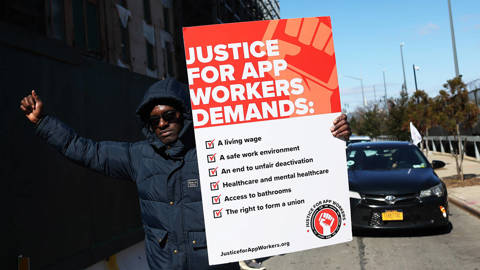

Recovering from both crises will require effective economic reconstruction to create jobs. In addition to restructuring the financial sector, recovery programs in the US, the United Kingdom, and other industrial countries hardest hit by the financial crisis must include relief for home and business owners, and job creation through infrastructure projects, clean-energy technologies, and improvements in healthcare and education.

In Afghanistan and Iraq, reconstruction must include not only the rehabilitation of services and infrastructure, but – more challenging – the creation of a macroeconomic, legal, and regulatory framework for effective policymaking. To avoid a continuation of conflict and aid-dependency, the main focus of the international aid commitment should be to reactivate small enterprises and promote startup companies in various sectors in order to create viable economies that enable people to earn a legal and decent living.

Despite their commonality, there has been a stark contrast in approaches to resolving these two crises. While programs in industrial and emerging economies aimed at addressing the financial crisis have been broadly debated at the national and international level, the debate about Afghanistan and Iraq has been narrowly focused on military and security issues, undermining the need for a major effort at effective reconstruction.

Interestingly, whereas most Americans are well aware of the $700 billion price tag for restructuring banks and the $787 billion stimulus package, far less attention has been paid to the almost $1 trillion spent on the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Many assume that the cost is so high because reconstruction is expensive. But only 6% of this amount was allocated for reconstruction and other aid programs. The rest was allocated to the US Department of Defense as a supplement to its annual budget, which has been between $500 and $650 billion in recent years.

World leaders should recognize that a larger investment in reconstruction, together with a comprehensive and well-balanced strategy to ensure accountability and appropriate policies for lawful employment, could have prevented these vast military expenditures, both in Iraq since 2006 and in Afghanistan since the Taliban government was ousted in 2001.

Just as world leaders have led the global discussion on policies to resolve the financial crisis, they should start a broad-based debate on the international community’s future involvement in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other war-torn countries, where better living conditions are needed to give the local population a stake in the peace process. The international community should recognize that military, security, and peacekeeping operations are costly and will not succeed in the absence of new, innovative, and integrated strategies for economic reconstruction.

NEW YORK – Policymakers, academics, and journalists usually discuss the global financial crisis and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as if they somehow exist on parallel tracks. But today’s financial and foreign-affairs crises are in fact closely linked. Indeed, the way the world has sought to resolve the financial crisis offers interesting insights about how the foreign-affairs crisis should be approached.

Today’s foreign-affairs crisis goes well beyond Afghanistan and Iraq. The record of countries that move from conflict to a fragile peace through military intervention or negotiated settlements is dismal: roughly half of them revert to conflict, leading to more human tragedy and large numbers of refugees. Moreover, failed states are an incubator for terrorism, trafficking of drugs and people, piracy, and other illicit activities. Of the half that remains at peace, the large majority end up highly dependent on foreign aid – hardly a sustainable model in the context of the global financial crisis.

The two crises have created immense human suffering worldwide: thousands of families have lost loved ones in wars, and the financial crisis has taken people’s jobs, livelihoods, assets, pensions, and dreams, as well as worsening fiscal and debt conditions in most industrial countries. As a result, taxpayers in donor countries are demanding more transparency and accountability in how their money is spent both domestically and abroad – and rightly so.

There are notable links between the two crises. The war in Iraq contributed in part to the increase in oil prices from $35 per barrel in 2003 to $140 in 2007. This increase put pressure on businesses and consumers, and was a major factor in the increase in world food prices. As prices went up and recessionary pressures increased, many homeowners failed to pay their mortgages. The sub-prime sector in the United States was hit, and the financial crisis spread from there.

Both crises require policymaking that departs from “business as usual.” Short-term emergency policies are needed to deal with high unemployment, home foreclosures, business bankruptcies, and often with hunger, disease, and a number of other ills. Emergency or humanitarian policies may improve basic consumption in the short run, but they may also discourage investment, increase inflation, and lower prospects for economic in the long run. As a result, such policies should be discontinued as soon as possible.

Recovering from both crises will require effective economic reconstruction to create jobs. In addition to restructuring the financial sector, recovery programs in the US, the United Kingdom, and other industrial countries hardest hit by the financial crisis must include relief for home and business owners, and job creation through infrastructure projects, clean-energy technologies, and improvements in healthcare and education.

SPRING SALE: Save 40% on all new Digital or Digital Plus subscriptions

Subscribe now to gain greater access to Project Syndicate – including every commentary and our entire On Point suite of subscriber-exclusive content – starting at just $49.99.

Subscribe Now

In Afghanistan and Iraq, reconstruction must include not only the rehabilitation of services and infrastructure, but – more challenging – the creation of a macroeconomic, legal, and regulatory framework for effective policymaking. To avoid a continuation of conflict and aid-dependency, the main focus of the international aid commitment should be to reactivate small enterprises and promote startup companies in various sectors in order to create viable economies that enable people to earn a legal and decent living.

Despite their commonality, there has been a stark contrast in approaches to resolving these two crises. While programs in industrial and emerging economies aimed at addressing the financial crisis have been broadly debated at the national and international level, the debate about Afghanistan and Iraq has been narrowly focused on military and security issues, undermining the need for a major effort at effective reconstruction.

Interestingly, whereas most Americans are well aware of the $700 billion price tag for restructuring banks and the $787 billion stimulus package, far less attention has been paid to the almost $1 trillion spent on the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Many assume that the cost is so high because reconstruction is expensive. But only 6% of this amount was allocated for reconstruction and other aid programs. The rest was allocated to the US Department of Defense as a supplement to its annual budget, which has been between $500 and $650 billion in recent years.

World leaders should recognize that a larger investment in reconstruction, together with a comprehensive and well-balanced strategy to ensure accountability and appropriate policies for lawful employment, could have prevented these vast military expenditures, both in Iraq since 2006 and in Afghanistan since the Taliban government was ousted in 2001.

Just as world leaders have led the global discussion on policies to resolve the financial crisis, they should start a broad-based debate on the international community’s future involvement in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other war-torn countries, where better living conditions are needed to give the local population a stake in the peace process. The international community should recognize that military, security, and peacekeeping operations are costly and will not succeed in the absence of new, innovative, and integrated strategies for economic reconstruction.